A village packed with ancient artefacts and goldmines, plus a plethora of miraculous churches and Cyprus’ very first seismological station

Mathiatis may not be the centre of the universe, but it is certainly considered to be the ‘centre of balance’ in Cyprus, and that’s not just according to local calculations: the British also chose it in the 19th century for its central position.

“It is the centre of Cyprus. When the English came, they set up headquarters in Mathiatis because it was the centre of Cyprus,” says community leader Theodoros Kyriakou Tsatsos.

They made a very good choice, because Mathiatis is packed with history, from ancient artefacts and goldmines to a plethora of miraculous churches and catacombs.

Standing outside the new Apostle Varnavas church, built in 2001 for the growing community of 1,000 residents, and looking to the hill opposite, you can see the island’s first seismological station.

Nearby is Kyprovasa – from the words Cyprus and possibly base or valley from the ancient Greek ‘vassa’ – the remains of an old settlement from Lusignan and Venetian rule, which was destroyed by the Ottomans when they conquered the island in 1570.

Coffeeshop rationale places Mathiatis – 22km south of Nicosia – at Cyprus’ centre of balance, hence the choice of Mathiatis as the location of the first seismological station, backed by taking Kyprovasa to mean ‘centre of Cyprus’.

The Mathiatis station started operating in 1984 and now works unmanned, receiving data and sending it to headquarters.

Having established Mathiatis’ pivotal position, it’s time to get to know this ‘factory’ of culture from its birth.

Everything here has a story.

Its history begins before you even reach the village, with ancient mines on either side.

The oldest one is Strongylos, a gold mine to the south of the village, dated 600BC, also a Unesco world cultural heritage candidate, with its mysterious dark galleries running deep into the hill. The other is Kokkinoantonis to the north of the village, used more recently to mine gold, silver, copper and iron, in that order.

These sites have also produced a large collection of unique artefacts and attract university students from all over the world. Both mines are accessible to visitors.

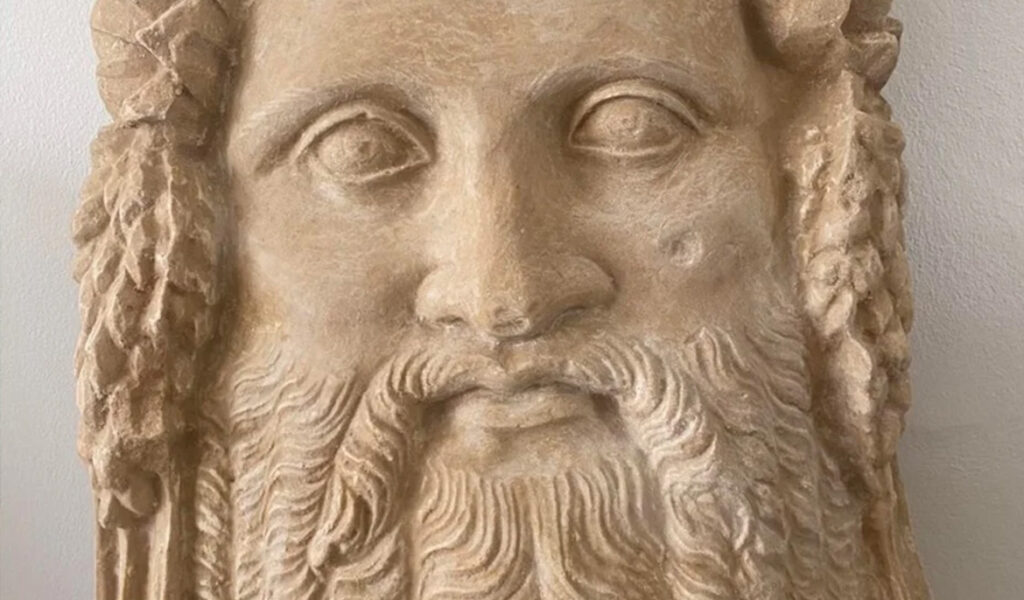

One of the artefacts found at Strongylos is the carved limestone head of Bacchus Dionysus dated circa 200BC, now exhibited at the archaeological museum in Nicosia and once used as the Cyprus Theatrical Organisation’s logo.

The carved head is a plaque 51.2cm tall and 11cm thick. It was once coloured, as tiny remnants of purple and green paint can still be seen.

It is also believed that there were volcanos in the area in antiquity. Today, when fields are ploughed, they churn up rock fragments in deep burgundy and rich green.

When the Ottomans sold Cyprus to the English in 1878, Mathiatis was initially chosen to house the colonial administration, as the village offered a moderate climate and its location and environment served as a natural fortress.

The only proof still visible today of their presence is the English cemetery outside the village, a rectangular area surrounded by a stone wall and shaded by tall trees.

Every village resident has a story to tell, which enlivens the atmosphere at the kafenio over coffee and backgammon.

Most are associated with the island’s religious heritage, of which Mathiatis has a good share. After all, historians and writers refer to Cyprus as the Island of Saints.

“We have an unusually high number of churches for a small community,” Tsatsos said.

Inbound from Nicosia, the first church you see is Saint Paraskevi, built in 1728. The ceiling is inlaid with 22 plates believed to represent the 22 Christian families living nearby at the time it was built. Saint Paraskevi is believed to help with eye problems.

Further back is the out-of-sight church of Panayia Galaktotrofousa. It is unknown when this church, now housed within the walls of the cemetery, was built. Mothers prayed to Panagia Galaktotrofousa to be able to breast feed. The original icons – hundreds of years old – are kept safe at Apostle Varnavas church.

But under the church is an even less-known place of worship, a catacomb believed to have been used by the Catholics during Ottoman rule between 1571 and 1878.

Within the catacomb, an icon of Panayia was found, along with holy water which is channelled to a small reservoir. Today, the catacomb is lined with icons, candles and requests to the saints.

Saint Eftychios, on the way to Sia, was a heap of stones on a knoll for years, with no testimony to the monastery that once housed the chapel.

According to historians, Saint Eftychios was one of the 300 clergy and laity – also known as Alamanos – who sought refuge in Cyprus, after being persecuted by the Arabs in 638AD after the siege of Jerusalem. In Cyprus, they dispersed into smaller groups.

Along with other monks, he built a monastery dedicated to Saint Eftychios. In 1571 the Turks killed the monks, destroyed the monastery and left the chapel in ruins.

A Mathiatis resident – Kyriakos Shengerlengos – found an icon of Saint Eftychios in the rubble a few decades ago and kept it for safety in his house. The icon was handed down from generation to generation and is now kept at Apostle Varnavas church. It is believed to be around a thousand years old.

The community has now restored the chapel to its original state with the help of the Department of Antiquities.

Yet another church – Saint Irene Chrysovalantou – was built some 40 years ago by a couple that for 12 years couldn’t conceive. Omiros and Anastasia travelled to Greece and prayed to Saint Irene Chrysovalantou to grant them a child.

Upon their return to Cyprus, they began building a church in the saint’s name to the north of the village. A few months later Anastasia was pregnant. Unfortunately, Omiros died shortly after their daughter was born.

On the exterior are mosaics signed by Cypriot artist George Kepolas.

Then, there is also the church dedicated to Saint Ephraim, which was built in recent years and attracts thousands of visitors.

“This church is built exclusively with stone in the 16th century style. There is no iron or cement, not even in the foundations,” Tsatsos said.

“It attracts around 10,000 visitors per month and is considered to be miraculous.”

All are interspersed with newer churches – some replicas of churches in the north and others built to honour specific saints – ancient mills and aqueducts, the community dam, farms, solitary homes, army camps and parts of the original road leading to the village.

One of the newest – Egyptian Coptic – dedicated to Archangel Michael is currently being built.

On Sundays, Mathiatis is frequented by cyclists for the cooler temperatures and scenic routes. The village is also a favourite among scouts, who organise expeditions and survival courses in the countryside, as well as hikers.

Mathiatis is not only church mad, it is also quite possibly the cleanest village in Cyprus, winning numerous environmental awards for recycling and cleanliness. The community makes sure the village always looks its best.

“We have won consecutive first prizes for cleanliness in the Nicosia district from 2011 till 2023 and the green award for Cyprus in 2021. In 2015 we won the Cyprus environmental award for the complex of villages Mathiatis belongs to,” says Tsatsos proudly.

Mathiatis has even won Cyprus-wide awards for recycling cooking oil.

Mathiatis keeps on growing and improving. In the community’s plans are a new park and sports facility with futsal fields, as well as nature walks and viewing points that will include the ancient mills and mines.

It also has an enthusiastic community leader in Tsatos who points visitors in the right direction to see all the sights.

“I can give visitors a tour if they call beforehand,” he says, adding there are books available in Greek for anyone interested.

“We don’t sell them. We give them to whoever wants one.”

If you’re planning a visit or just want to delve deeper, give the community council a call beforehand on 22540028 or visit Mathiatis’ website https://www.mathiatis.com/en