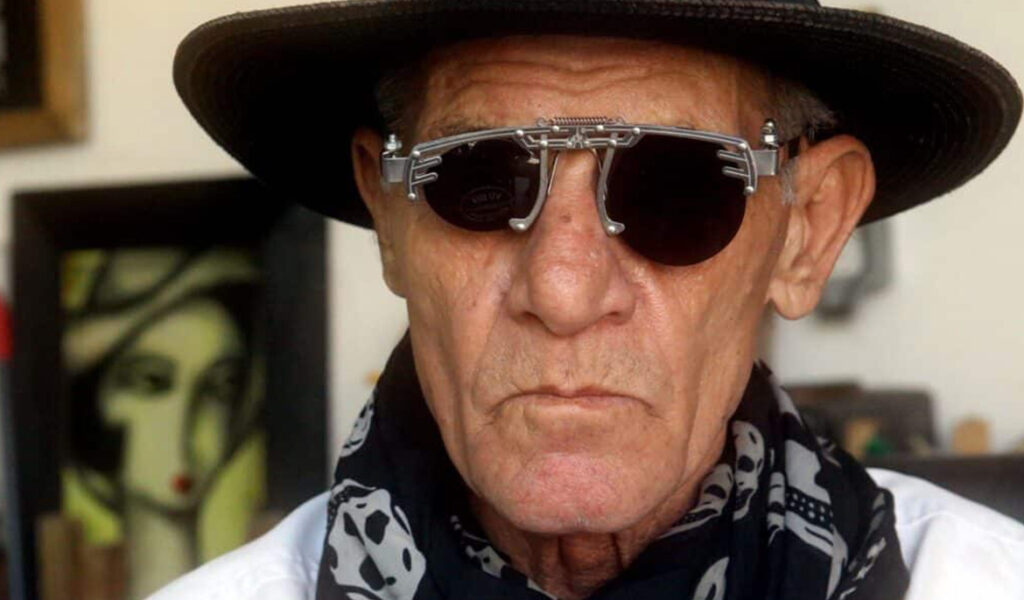

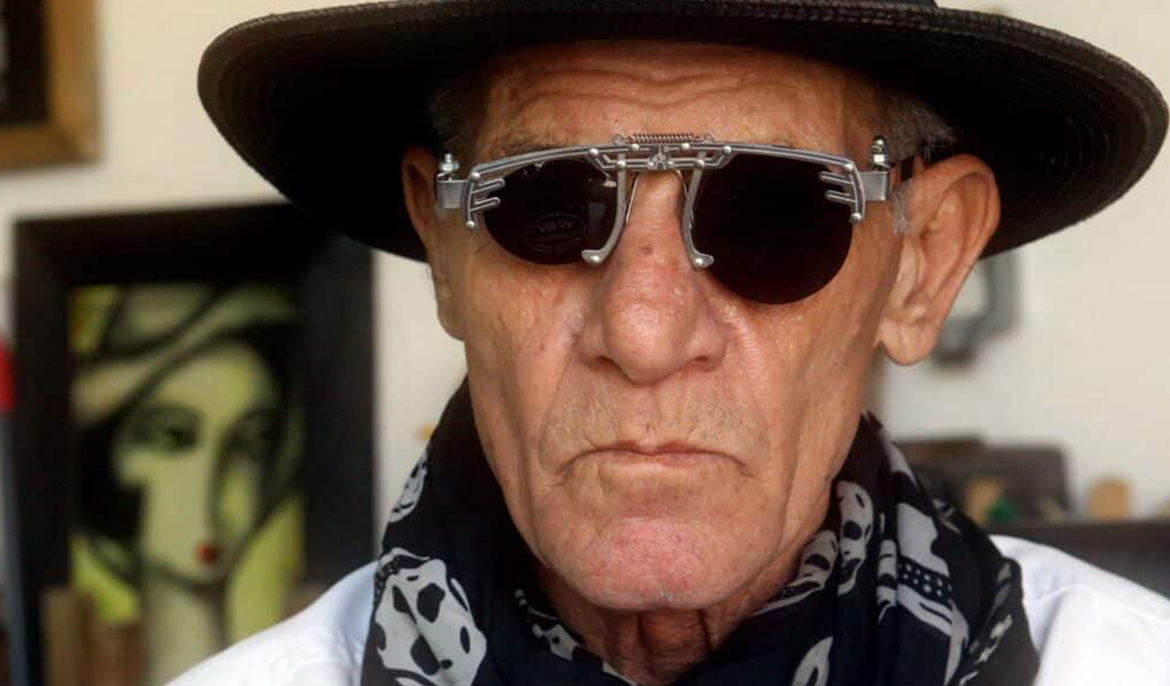

From partying in LA to a semi-rural life in Larnaca, one man is always dressed to impress. THEO PANAYIDES finds him where art and engineering meet

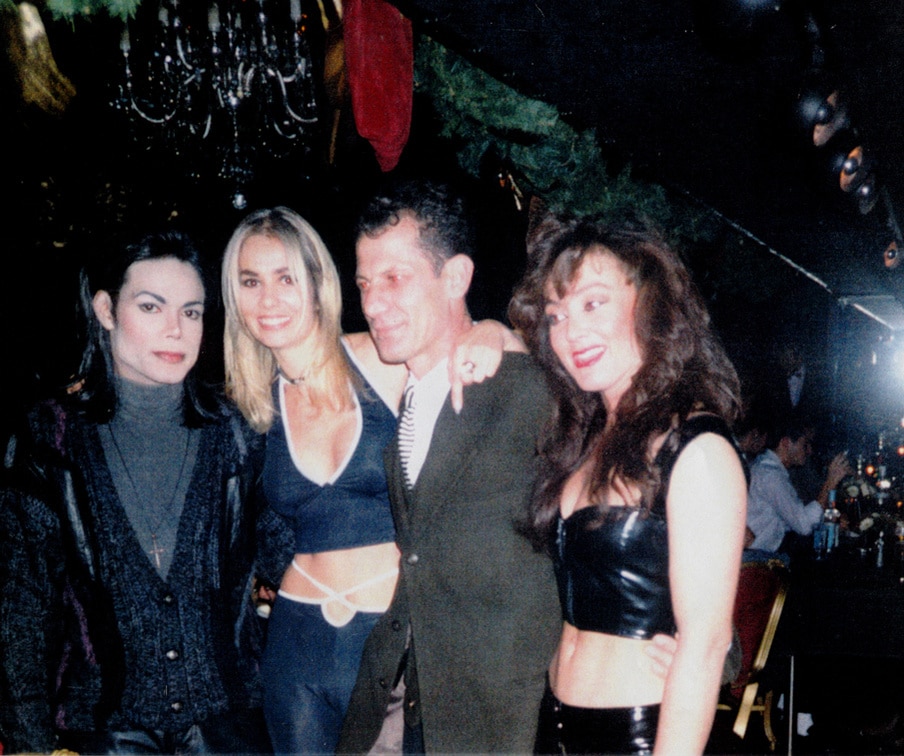

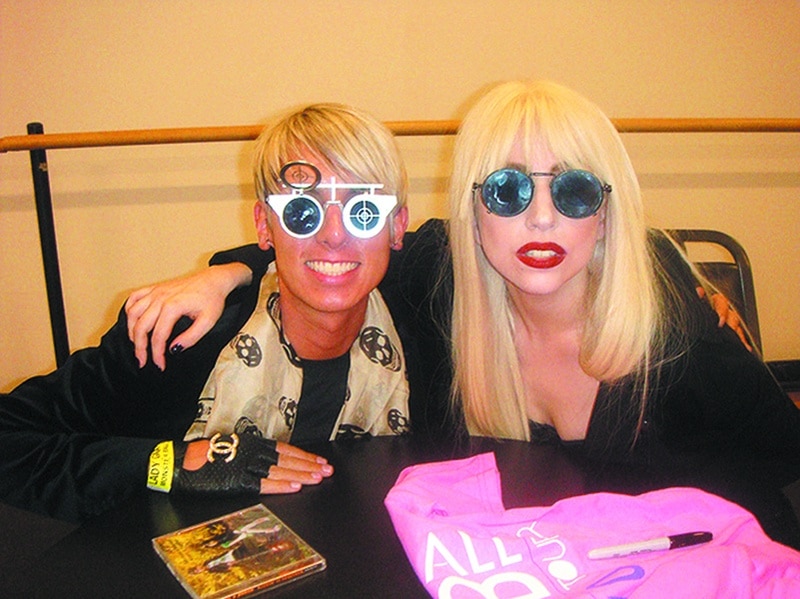

There’s a phrase that recurs in my conversation with 72-year-old Hi Tek Alexander (né Alexandros Tasou): “You cannot believe [it]”. It pops up now and then, a few days before an exhibition – on May 1, at MOLA Culture Factory in Lefkara – showcasing some of his designs for the first time in Cyprus. It appears, unbidden, as he looks back on his glamorous life – from founding a world-famous fashion brand, to working with the likes of Michael Jackson and Lady Gaga.

“I was a rich guy once. 100 million,” he recalls in fluent but non-native English. “I was super-rich. I had everything – yachts, everything. Two Bentleys – I had many things. Many women. You cannot believe.

“I lived with Miss Universe in my house, all the Miss Universes. If you ask Anna Vissi – if you ever have a chat with her – tell her, ‘You went to this guy’s house? Were all the Misses from the whole world in this house?’, she’ll tell you ‘Yeah’.” This was in LA, when Alexander’s place was apparently one long party. The Miss Universe girls came to party – then got blind drunk, and puked on the floor. “They looked disgusting, without makeup,” he says, shaking his head disapprovingly. “They looked so ugly. You cannot believe.”

The memory is poignant, especially because of our surroundings: an old village-style house in a forgotten, almost semi-rural corner of Larnaca. This is where Hi Tek Alexander lives these days, amid narrow storerooms piled high with boxes (they contain hats, glasses, watches, you name it), punctuated by the squeals and giggles of the very young children – a four-year-old son and a one-year-old daughter – he’s fathered with his Chinese wife Qian, a.k.a. ‘Zoe’.

From beauty queens in an LA mansion to this mundane setting? You cannot believe. But in fact, even beyond the photos and videos commemorating his past – many of them collected on his website (http://www.alexanderhitek.com) – there’s even more tangible proof in the cluttered backyard: the aforementioned two Bentleys, a white one and a blue one, reclining in 40-year-old elegance among the detritus like a pair of bored princesses in the lobby of a two-star hotel.

Alexander drives us down to Finikoudes in the white Bentley, for his daily espresso at Costa Coffee. I presume he gets some curious looks when he goes into town – not just for the car but also his appearance, rail-thin and dressed to impress. This morning he’s a kind of human chessboard – black trousers, white top, black scarf with a white skull pattern – the whole look designed to set off his black-and-white loafers, which any pop fan will instantly recognise: Michael Jackson shoes.

He knew Michael Jackson, right? “I stayed with Michael Jackson for six months,” he replies. “I worked with him for many videos.” That said, “you will not see my name – you see ‘Armani’. Why? Armani paid the money. You understand? The big companies pay money to get the publicity – but the people who do the work is people like me.”

MJ was quite eccentric, wasn’t he?

“Not really. He was a normal guy… Don’t listen to all the bullshit stories.” Even Bubbles the famous chimpanzee was there for a reason, to help Michael “learn the movements of dancing” in a more primal way. “He was a very smart guy. He was not stupid.”

Hi Tek appreciated Michael (the feeling was apparently mutual); Madonna, not so much. “I knew Madonna before she was Madonna. I met her in Tokyo. She was…” He sighs at the memory: “They were trying to promote her, and I didn’t even like her”. The much older Warren Beatty – her boyfriend at the time – was using all his influence to make her happen. Alexander thought her unattractive, and wondered what the secret of her success was.

“I asked the Japanese [guy] from the TV, I asked him, ‘I don’t know these people, who are they?’. He said, ‘This is Madonna, she’s going to be a big star… That’s the boyfriend, Warren Beatty, he invests the money’. I said, ‘Why? She’s ugly’. He said, ‘She’s a good cocksucker’. I thought ooh, that’s the business!” Alexander laughs dryly. “I have a video with her.”

He’s an unusual man, alternately shy and unfiltered, shifting his body and gesticulating violently as he talks; some of his political views would surely get him cancelled in today’s quote-unquote polite society. In his day, however – the 80s and 90s, right up until the internet came and (he says) ruined his business model – he wasn’t just successful but iconic, the Hi Tek Designs brand associated with a very specific look: steampunk, futuristic, industrial.

His glasses looked like goggles, or optometrist’s masks. His watches rotated like nautical instruments. His style was surreal (asked for influences, he cites Man Ray and Salvador Dali), conflating art and engineering; one of his first big successes, presented at the London Clothes Show in Kensington, were ‘telephone handbags’, with a telephone receiver as the handle and the dial as the buckle. (A few will be on show at the exhibition in Lefkara this week.) Some years later, when mobile phones were taking over in Cyprus, he bought half a million old phones from Cyta at $0.50 each – much to the amusement of Cyta officials, who openly mocked him – turned them into handbags, then sold them in Japan for C£120 each.

That’s a whole other issue, the Cyprus connection. “My name is Alexander. I was born in Greece,” is how he introduces himself in an old video (“I live in England now for 22 years,” he adds, dating the video to the mid-90s) – yet in fact he was born in Cyprus, actually at the tip of the Karpas peninsula near Apostolos Andreas monastery, during the solar eclipse of September 1, 1951.

“Spiritually, mentally, I’m in Cyprus for 72 years,” he admits. He’d always visit regularly, even before coming back to live with Zoe a few years ago – yet his version of Cyprus is different to most people’s. He never once mentioned the island as his birthplace during his years abroad, calling himself simply Greek. “I don’t feel Cypriot, I feel Greek,” he explains. “I don’t believe Cyprus is even a country. Cyprus belongs to Greece.”

His take on Cypriots is equally ambivalent; they’ve changed since his own village days, “they’re not the Cypriots I knew”. His dream of opening a fashion school got scotched by bureaucracy, nor is his work really known or appreciated. (There’s a reason why the upcoming exhibition is his first on the island.) Once, as an experiment, he left one of his telephone bags on the street at Finikoudes, just to see what would happen; people were “afraid to touch,” he reports with contemptuous glee, it was too weird for them. “The Cypriot needs halloumi, lountza, olives. The Cypriot cares about his stomach. He doesn’t care about these things.”

He took off as a teenager, going off to see the world. “I just wanted the Marco Polo test, you know? I was adventurous, I wanted to go.” Stories from his life come thick and fast, so much so that you start to wonder if he might be exaggerating – thus, for instance, he says there are “50 cats” at the old house in Larnaca then later, recalling his experience of Communist-era Romania as an 18-year-old, he mentions sleeping with a girl he’d just met then waking up to find there were “50 people” sleeping in the flat. Are the numbers accurate, or is ‘50’ just shorthand for ‘a lot’ here? Then again, there’s a lot of cats at the old house in Larnaca.

He spent a year in an Israeli kibbutz, in 1967. He stayed with Pierre Cardin (“my teacher”) for a year and a half. He worked for the Nigerian commerce ministry “as an advisor for purchasing goods for the government,” witnessing high-level corruption – both by Brits and Nigerians – up close. (He’d travel to Lagos every weekend carrying cash in a diplomatic bag then fly back to London, pocketing “maybe $30-40,000” for his trouble.) He made $50 million in a month when America invaded Iraq, having been slipped some inside intel by his Greek shipping-tycoon friends. He went to Thailand in his Marco Polo days, and was shocked by the loose morals – “They were selling the children for £5 in the street, like we sell the pigs… I said ‘There is no God in this place!’” – then to China in 1968, when the locals were still riding bicycles.

At some point he bought a factory in China, from the military, “in Shenzhen before Shenzhen was a city, it was a small fishing village”. He had some experience, his grandfather having owned a similar factory in Famagusta. “I employed 500 women. At that time it was $1 a day, plus food and sleep.” (Zoe, who’s quite a bit younger, worked for him for 10 years, as a translator, before they became a couple.) They made watch parts, which were sent to London for assembly – his first real business, though celebrity status came later.

Hi Tek’s biggest market was undoubtedly Japan, a triumphant collaboration with Fuji TV in the late 1980s netting him an overnight fortune. “I went out of my head,” he recalls wryly. “I was very young, I had no experience with money… So I spent the money very fast.”

Did he pick up any bad habits?

“Mainly alcohol. Mainly socially – one bottle of whisky a day, with coffee. With my customers. A day! Every day. This lasted for about 20 years and then I stopped, completely… My doctor told me, ‘You stop or you die, what d’you want?’. So okay, I stopped.”

By that time there were 15 Hi Tek shops all over the world, plus concessions in various department stores – “Macy’s [in New York] had a special section: 25 metres, next to Harley Davidson” – and he was working in movies and music. “They wore my masks, my sunglasses. All the top musicians, even from the Greek side” – even the aforementioned Anna Vissi, who stayed at his place in LA (with the various Miss Universes) while trying to break into the American market.

The life wanes and waxes, the man remains. All this information helps a little bit in understanding Alexandros Tasou – but it’s really his personal energy that stays in the mind: the odd mix of candour and awkwardness, the intense body language, the occasional outbursts and cryptic asides, the sense of a very special mind ticking away.

For all the adventurousness, there’s a certain austere streak too. It doesn’t really come as a surprise to learn that, had he not become a fashion designer, he’d have liked to be a priest. (Growing up near the monastery, he’d often see pilgrims literally crawling on their knees to go kiss the icons; “It was a different time”.) There are things of which he disapproves – whether it’s Madonna or the loose morals of 1960s Thailand – and he does get frustrated, though “not with people outside my house, only in my house. Why? Because, if they do something wrong, I feel I need to correct them”. Despite – or because of – his genius, he can’t be easy to live with.

And of course he’s also living now, in the old house in Larnaca, with a wife and two young kids to take care of. (Zoe is actually his fourth wife – though he has no other children, and none of the previous marriages seem to have lasted very long.) It can’t be easy becoming a dad at his age. “I want to live at least until my son is 15,” he replies soberly, “so I can teach him my work.” He still makes fashion, though the factory in China closed down and it’s just him and Zoe here: “Most of the stuff is unassembled, so I assemble them here. I have all my screws and my tools”. I recall the narrow storerooms piled high with stuff, online sales starting to pick up after Covid.

“I don’t really want to work,” shrugs the man known as Hi Tek Alexander. “I just want to teach my wife to teach my son, in case I die.” It’s a little bit sad, then again he still has the Bentleys, and a certain innate sense of style – and of course his memories, MJ and Madonna, acclaim and creativity and the fashion world in thrall to his designs. Believe it. khmertimeskh