Life wasn’t easy for this artist. But his deep love for the island and remarkable talent have left a legacy that most of us will instantly recognise

Every postcard, mug, ashtray or keyring that depicts a map of Cyprus is likely based on the work of one man: an artist who – though forced from the island time and again – always returned.

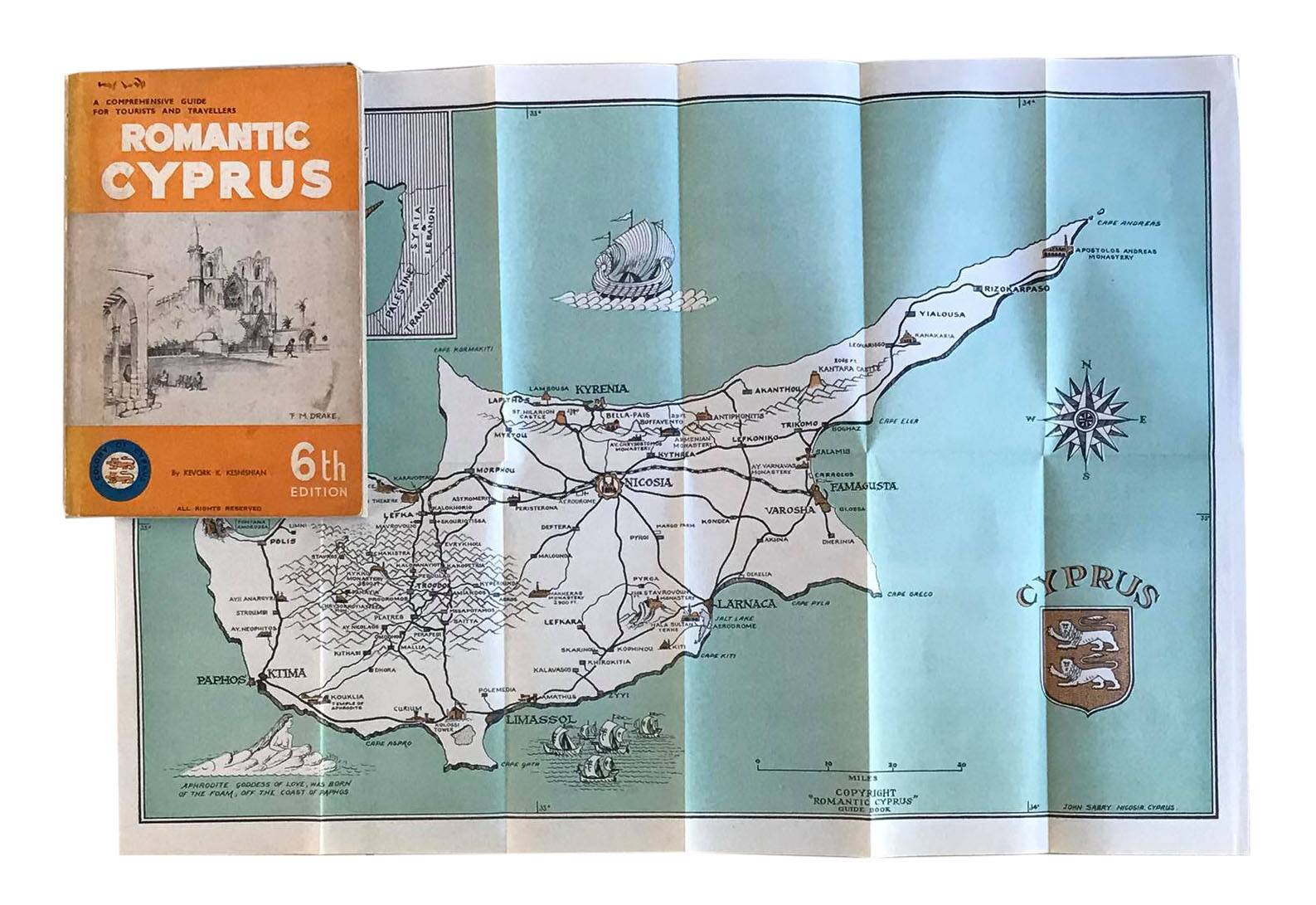

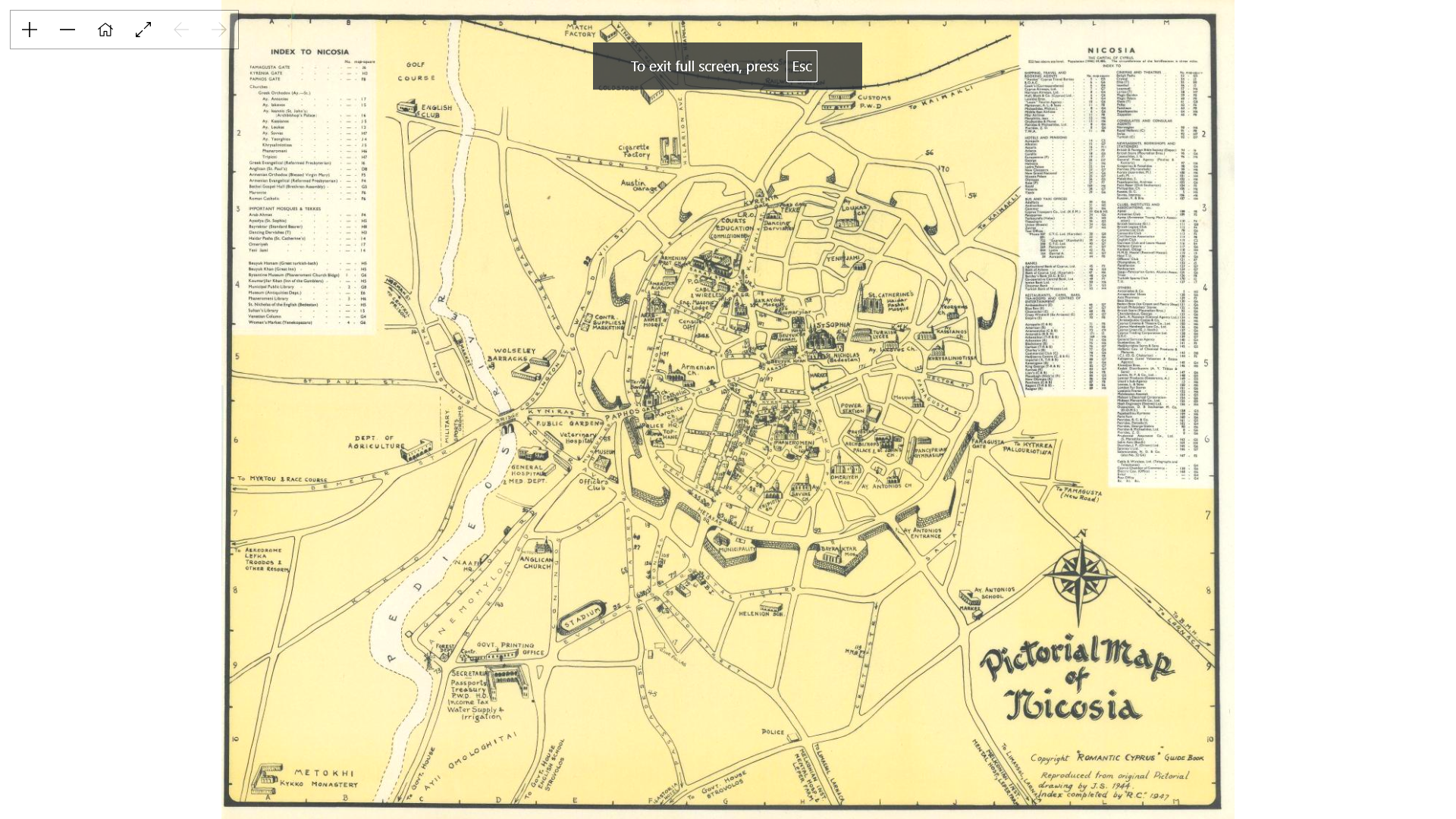

His artwork encapsulates a golden era of Cyprus: everyday scenes of family and friends, as well as evocative paintings of Kyrenia, Karpas and Bellapais before the war. His paintings hang in galleries around the world; his illustrations secure high prices at auctions. And he painted the first modern maps of the island: originally commissioned for use in Romantic Cyprus (first published in the 1940s, the well-known guidebook ran to almost 20 editions), these maps quickly became a staple on local souvenirs.

Meet John Sabry, painter, photographer and cartographer. Born in Kyrenia in 1914, he passed away in 2006 at his home in Lemba. And, like his artwork, every facet of his remarkable life is tied to a deep love of Cyprus.

“My dad grew up very poor, as many people were at that time,” reveals his daughter, Katie. “And his life was far from easy. He’d tell me stories about how he was always drawing and painting as a child. He’d go out into the villages, paint watercolours of wildflowers and landscapes and everyday scenes, and then jump on his bicycle and sell his work door to door!”

Over time, as he gained recognition, John was commissioned by magazines to create hand-drawn graphic art, designs and illustrations. His maps of Cyprus – intricately detailed, dotted with sketches of everything from agricultural workers to heraldic crests – have appeared in any number of books and exhibitions. And Katie, a well-known artist in her own right, often watercolours these original maps and sells them to global collectors.

For the most part, these maps were created after WWII: during the war, John joined the Cyprus regiment and was posted to North Africa and Italy.

“But when he was demobbed at Polemidia in 1945, he immediately took up art again!” says Katie. “And started working once more on the town maps for Romantic Cyprus.”

This book ran to multiple editions over the years, and the beautifully composed pull-out maps that have been copied onto so many souvenirs are all John’s work. But his life itself was not so composed.

“Whose was, in those times?” asks Katie. “Yes, after he left the army he was able to continue with his art, and he met and married my mother when she visited her sister in Nicosia. She was a draughtswoman,” Katie adds, “and started working at the Nicosia Public Works Department. I remember her talking about measuring the Venetian Walls for a project; she was stunned they were not one millimetre out!”

In 1955, wary of the troubles, the artistic couple moved to the UK. But within a couple of years, they were back. “Neither could stay away for long!” smiles Katie.

The Sabry family lived in Ayios Dometios until 1960; then Kyrenia until 1964.

“Occasionally, we returned to England for a few months,” says Katie. “It was a hairy time on the island; I remember shootings each night, endless curfews, and trips to Nicosia that took us all the way along the west coast and back when the Hilarion Pass was taken!”

By this time John’s work had been exhibited at the Royal Academy Summer show in London, and he’d won National Geographic awards for his photos, so constant commissions were ensuring a steady income. And, in 1972, the Sabrys moved into their own home, close to the Kyrenia castle…

“Despite the troubles, it was a happy time for us,” says Katie. “Yes, there were signs that all was not well – dreadful shootings and such. But I was a teenager, wild and free and about to study art in Italy. Life felt perfect!”

With the invasion, life for the Sabry family came crashing down. In the summer of 1974, Katie was evacuated to London, while parents John and Dorothy went first to a refugee camp in Dhekelia and then to the UK.

“But they couldn’t stay away,” says Katie. “They came back to Cyprus overland, by bus and ferry. And, because they both had British passports, they managed to talk their way across the border. Apparently, my Mum lied through her teeth to the border guard, saying she was a close personal friend of Denktash!”

Katie recalls joining her parents in 1975 – “they used one of my Dad’s paintings to bribe a guard to let me across the border; I’d love to know where it ended up!” – and the family took possession of their home in Kyrenia.

“But it was such a strange, surreal existence,” Katie recalls. “Our Cypriot neighbours had fled; their homes bombed out and occupied. Once more, my parents knew they’d have to leave – they stayed only until we could get my Dad’s artwork out; smuggled on a container ship to Marseille.”

John Sabry in 1957

As refugees, the family moved first to France, then Suffolk, and finally, in 1979, back to Paphos.

“Nothing was going to keep my Dad from Cyprus,” says Katie. “He may have been from a mixed background – Kurdish, Syrian, Egyptian and Turkish Cypriot – but he identified as Cypriot. That’s who he was, through and through. The island was in his blood. And every day until he died, he’d paint Cyprus.”

Today, John’s legacy lives on in his family: daughter Katie Sabry and grandson Alex Welch are both well-known local artists. And, after his passing, Katie recovered her father’s unsold artworks from his home, including many of his hand-drawn maps of Cyprus – a testament to her father’s enduring love for his homeland.

It’s a love that continues to live on in every map, every painting, every memory he left behind. Even today, when we buy a keyring, ashtray, or postcard depicting Cyprus, we’re more than likely to be celebrating the spirit of John Sabry. An artist for whom Cyprus was forever home. And to whom it was everything.